Imprint

© Ľudovít Gráfel

Published: © Mestský úrad Komárno and NEC ARTE s. r. o., 1999, 2006. 66 p.

Design: Tibor Németh

Corrected: PhDr. Eva Dénesová, Mgr. Mikuláš Getler Eva Dénesová, Mgr. Mikuláš Getler

Translations: Zuzana Bódayová, Zuzana Sáfiová

Technical redactors: Ľudovít Gráfel, Tibor Németh

Reproduction: NEC ARTE s. r. o., Komárno – www.necarte.sk

Print: Bratislavské tlačiarne a.s., Polygrafia SAV, Bratislava

Photo authors: © Otto Kurucz, Oroszlámos György, Ľudovít Gráfel, Ladislav Platzner, Ladislav Vallach, Mária Sláviková, Peter Frátrič, Szamódy Zsolt, Teodor Nagy, archival documents of Podunajské múzeum v Komárne, Pamiatkový úrad SR v Bratislave, Mestský úrad v Komárne and private collection of Ing. Marián Reško.

FOREWORD

In recent years, we have witnessed an extraordinary and ever increasing interest in environmental issues and solutions, which is strongly related to the increasing attention in cultural monuments.

Cultural monuments determine the fundamental and long-term conformation of the environment. It is needless to emphasize that building and architectural sights play a dominant and primary role in forming our environment. This is fully true in case of the most important cultural monument of Komárno, the extensive fortification system, which has gradually been incorporated in the organic whole of the growing city and determined its urban development.

The whole fortification system in Komárno, which has been declared a national cultural monument, represents a significant building complex with relatively well preserved elements regarding historical fortification buildings in Slovakia. However, the diverse use of the individual fort elements, protruding forts and bastions is inappropriate. Not only does it prevent the monument to be presented as a complex or use its large spatial capacities for the benefit of the community, but it also devastates the fortress due to inappropriate intervention. From the view of monumental care, it is a favourable circumstance that despite the destruction and intervention, individual objects can be ideally and practically reconstructed on the basis of their preserved parts.

The projects and plans of the former Technical Directorate of Komárno (K.K. Genie Direction in Comorn), which can be found in the military archives in Vienna and Budapest, help us clarify the construction of this huge defence system. The Directorate in Komárno was established at the beginning of the 19th century and its highest institution was the General Directorate in Vienna (Genie und Fortifications Wesens or Directorium Generalis Rei Militaris Architectonicae).

At present, the elaboration of the fortification building from the 19th century is insufficient. Therefore, it is necessary to elaborate and publish the architectural-historical analysis of studies based on the study of historical materials and in-depth field researches.

Dear reader, when drawing up the pictorial part of this publication, I used 20 years of knowledge in the form of research, methodology of monument care and direct management of reconstruction works, as well as the presentation of the monument for the professional and the general public.

I am convinced that browsing through the pages of this book will motivate and increase the number of admirers of the fortress and also experts who carry out research work in this field. In this way, I allow the reader to gain further insights from the rich pictorial appendix.

I hope that it will gradually help us discover the secrets that are still hiding behind the walls of the fortresses in Komárno.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE FORTRESS IN KOMÁRNO FROM THE ANCIENT TIMES UNTIL THE MODERN TIMES

Because of the trading and military importance of river crossings, they have played a strategically significant role for thousands of years. Komárno’s earlier settlements controlled the waterways of the Danube, Váh and Nitra rivers. Not only did they control the rivers, but also the roads that went through the Nitra River valley.

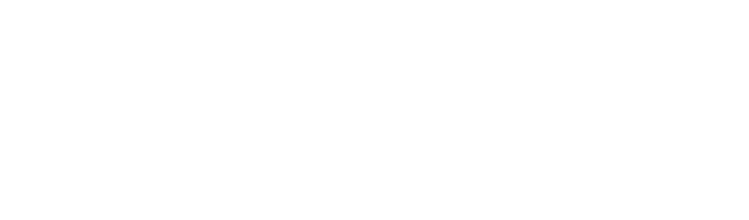

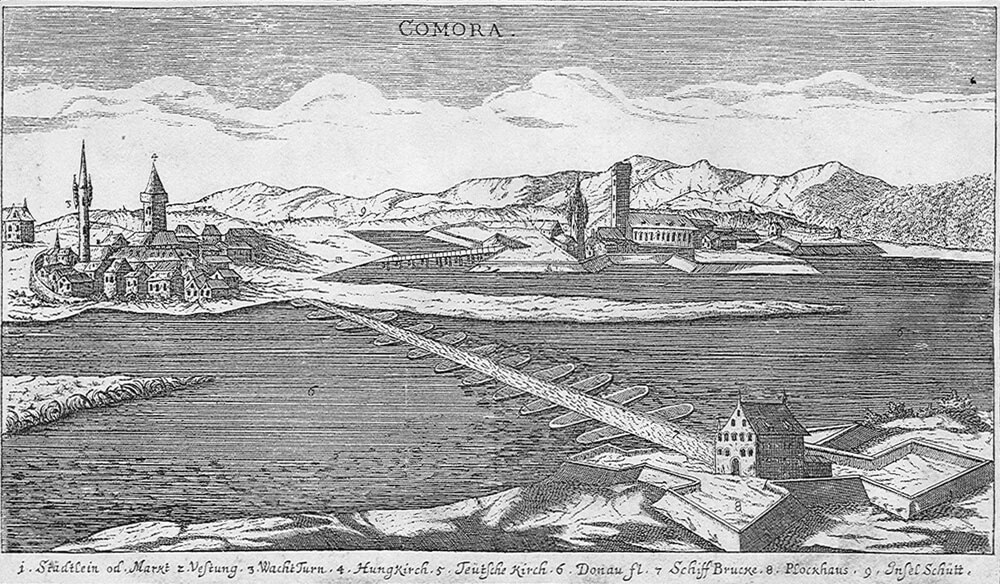

First depiction of St. Peter Palisade, which stood on the site of the present Fort Star (Danube Bridgehead)

2. Győrffy Gy.: A magyarok elődeiről és honfoglalásról. Budapest 1958, str. 108-109. “Anonymus” v diele Gesta Hungarorum píše nasledovné:”…nielen to dostal Ketel (Retel), ale omnoho viac, pretože vodca Árpád po podmanení celej Panónie mu daroval za vernú službu kus zeme na sútoku Dunaja a Váhu. Neskôr syn Ketela Alaptolma (Oluptulma) postavil na tomto mieste hrad (opevnenie)…“

3. Kecskés L.: Komárom erőrendszere. Műemlékvédelem roč. XXII, č. 3, Budapest 1978, str. 200.

4. Gyulai R.: Komárom vármegye és Komárom város történetéhez. Régészeti egylet 1890-évi jelentés, Komárno 1890, str.12-13.

5. Tok V.: Komárňanská pevnosť. Komárno 1974, str. 10.

6. Tok V.: c.d., str. 10.

7. Kecskés L.: c.d. str 200-201 Bonfini píše:”..ďalej na cípe ostrova vidíme veľkolepo vystavaný komárňanský hrad. Z jeho priestranných nádvorí sa vypínajú rozmerné paláce… Na brehu Dunaja kotví výletná loď menom Bucentaurus…”

8. Takács S.: Lapok egy kis város múltjából. Komárno 1886, str 88.

9. Takács S.: Hogyan ostromolta a komáromi bírót húszezer török vitéz? Komáromi Lapok roč. XXI., č. 7, Komárno 1890.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE FORTIFICATIONS UNTIL THE NAPOLEONIC WARS

After the invasion of Buda by the Turkish troops in 1541, Emperor Ferdinand I was forced to improve the fortification. He got back the castle in 1544 and ordered its extension. To prepare the plans of the fortress, he assigned Pietro Ferrabosco, who suggested a fort with more angles. This fortification system suited both the contemporary architectural aspirations and the configurations of terrain and hydrography.10. Testa, Castaldo and Decius are also considered to be the designers of the Komárno fortress.

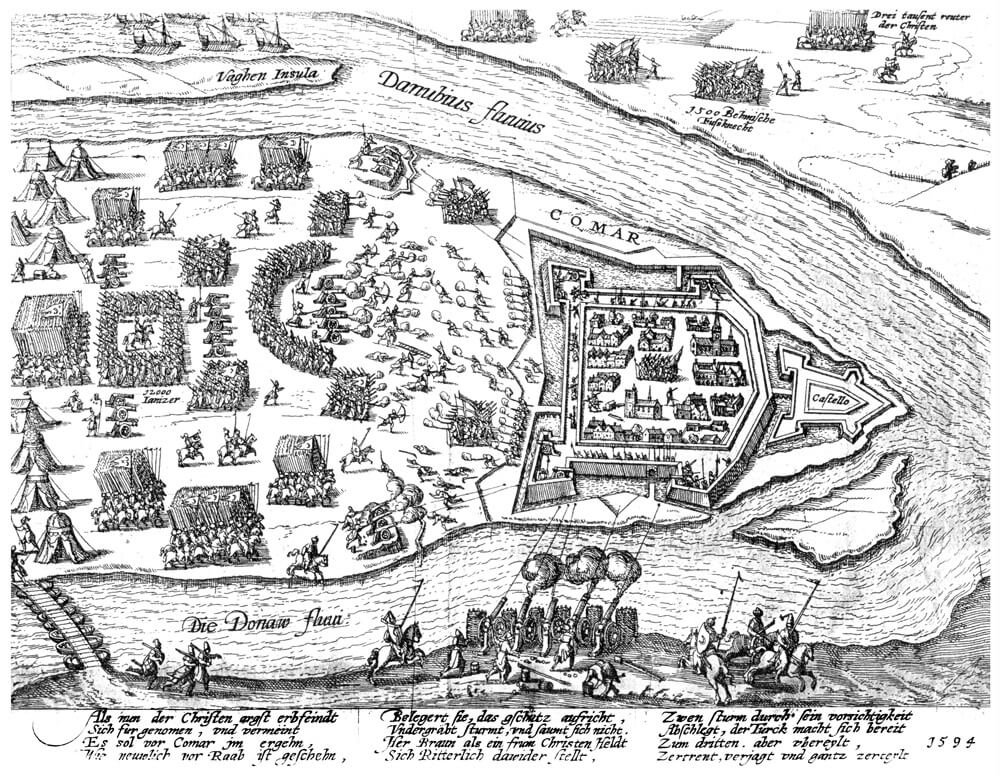

The first known sketch of the ground plan of the Old Fortress from 1572

The ground plan of the Old Fortress with marking the positions of the cannons on the bastions

Plan of rebuilding the Old Fortress between 1827 and 1839

Ground plan of the Old and New Fortresses from the end of the 17th century, presenting the names of individual fort elements (Engraving of Gaspar Bouttats based on the work of F. Wymes)

The Old Fortress and an eastern view of the city with the earth ramparts between them, built in 1528.

11. Kecskés L.: c.d. str.204.

12. Text pamätnej tabule na portálom Starej pevnosti: FERDIN ROM IMP GERMANIAE HUNGARIAE ET BOHEMIAE REX zc INFANS HISPANIAR ARCHIDUX AVS DVX BVRGVNDIAE ZC AD MDL.

13. Kecskés L.: c.d. str.204.

14. F.Wymes sa opieral o návrhy Carla Thetiho.

15. Kecskés L.: c.d. str.207.

16. Nápis na pamätnej tabuli nad vstupom do Novej pevnosti: LEOPOLDI: ELE: ROM: IMP: HUNG: AC: BOH: REGIS: ARCHID: AVS: -c: GVBERNATORE: COMMORNI: CAROLO: LVDOVICO: S: R: I: COMITE: AB HOFFKIRCHEN: BELLI: CONSILARIO: CAMMERARIO: COLLNELLO: GENERALI: CAMPI: MARESCHALLI: LOCVMTENENTE: -c: OPERA: OMNIA: EX: CESPITIBUS: CONSTRUCTA: IAMQ: DILAPSA: RESTAURAT: EXTERNA: AD: MELIOREM: DEFENSIONIS: STATUM: REDACTA: SUNT-ANNO: MDCLXXIII:

17. Kecskés L.: c.d. str.208.

18. Rovács A.: A Komáromi vár leszerelése. Komáromi Lapok roč. XXII., č. 30, Komárno 1901.

THE FORTIFICATION SYSTEM IN KOMÁRNO IN THE 19TH CENTURY

View of Komárno from the direction of St Peter Palisade

The surrounding area of Komárno from 1661

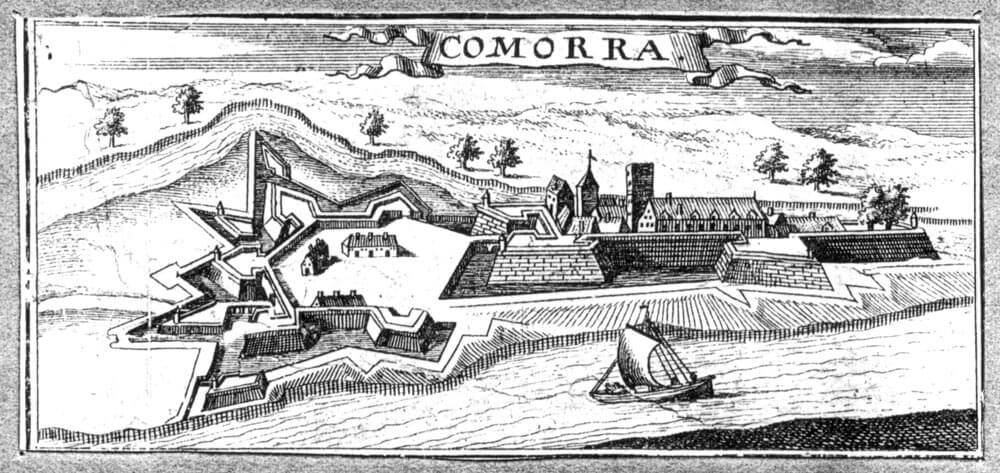

Glorious battles from 1848-49

Fights for the castle in Komárno in the revolutionary years of 1848-49

20. Údaj prevzatý z výkresu: “Rapports Plan – Uiber casematirung der alten Festung von 1827-1839.

21. František I. vyslovil želanie, aby komárňanská pevnosť bola najsilnejšou v celej monarchii a bola schopná poskytnúť útočisko dvestotisícovej armáde: “…als ein Haupt-Central-Depot-Platz für die ganze Monarchie…auch für eine zahlreiche Armee von 200 000 Mann in bomben freien Unterkunften daselbst in Sicherheit zu bringen” (Takács S.: Adalékok Komárom városának történetéhez és etnográfiához. Komáromi Lapok roč. VI.,č. 1, Komárno 1885).

THE PALATINE LINE

Draft of Bastion V with the ramps leading to the artillery positions from 1875

Graphic reconstruction of Bratislava Gate of Bastion I

23. Nielen ryhovaná hlaveň, ale i vynález záveru, ktorým sa uplatnil nový spôsob nabíjaniu zozadu. Apart from bastion I, the bastions of the Palatine Line are all symmetrical. The asymmetrical shape of bastion I is explained by its function, because it had to protect not only the bank of the river Danube but also the main gate of the town (Bratislava Gate) due to its position. The groundplans and sizes of bastions II and IV are exactly the same. Bastion III was the central bastion of the Palatine Line. Its ramparts and walls enclosed an angle that was more blunt than the adjoining bastions’angle. In the left wings of the earthen ramparts of bastions I, II and III, two-storey ammunition depots were established. In the conception of building the Palatine Line, they tried to blend the defence elements developed in the 16th and 17th centuries (heavy artillery defence on the façade, reinforced side parts) in one complex defence system. The walls of bastion II, which form a blunt angle, surround an empty interior. Its main part consists of the retranchement and a semicircular building, which has seven artillery casemates. The name “retranchement” was given and used by a famous French military engineer, Vauban, who planned this fort element in the second half of the 17th century. The two symmetrical wings of the retranchement closed an angle of 173° towards the forefield. Its side-wings stick out towards the body of the fortress, closing the gorge from inside. The width of the bastions in the Palatine Line is approximately 210 meters. Let’s see now the main measurements of bastion II for a more accurate orientation: gorge 210 meters, side-walls of the bastion 60 meters, front walls 108 meters, the front walls close a 145°-angle at the salient, and a 110°-angle at the corners. The height of the escarpment from the level of the ditch to the cornice is about 7 meters. The walls that strengthen the ramparts of the bastion are connected with the protruding side-wings of the retranchement. There is a gate on both sides of the retranchement. The interiors of the bastions in the Palatine Line are empty (not having been banked with earth), the width of their earth ramparts is approximately 23 meters, and a 10 meters –wide pathway was built on them for the cannons. We can approach the pathway from the interior on the side-ramps. The length of the route between the right and left flank of the bastion through the passages formed in the side of the contraescarpment is 540 meters – exclusive of the length of the retranchement. The length of both of the wings of the retranchement is 70 meters from the capital, 140 meters altogether. The protruding wings, both with lengths of 20 meters, are joined to these. Adding up the above mentioned figures, we can state that the length of the passages and casemates of a bastion is about 720 meters. If we add to this figure the length of the passages of approx. 370 meters formed in the fort walls which adjoin the bastions, we can conclude that the total length of the passages and casemates of the Palatine Line is about 5 km. 22. Bochenek Ryszard: Od palisád k podzemním pevnostem.Praha 1972.

24. Šesťreduitová línia tzv. Palatinal Verchanzungen je zachytená na pláne “Uibersichts Plan der alten und neuen Festung Comorn sammt Brückenkopfen und den Palatinal Verschanzungen”.

25. Obdobie výstavby dokazuje poznámku na pláne “Palatinal linie-No 274, K.u.K. Genie Direction in Komorn” z 24. februára 1870. Finally, we can state that the Palatine Line originates from uniting the previously developed, independent fort elements. The large number of loopholes formed for the small arms ammunition and heavy artillery emplacements, as well as the huge capacity of military quarters, acknowledge that the Palatine Line was a unique masterpiece of its era.

THE VÁH LINE

Bird’s eye view of Bastion IV in the 1930s z tridsiatych rokov nášho storočia.

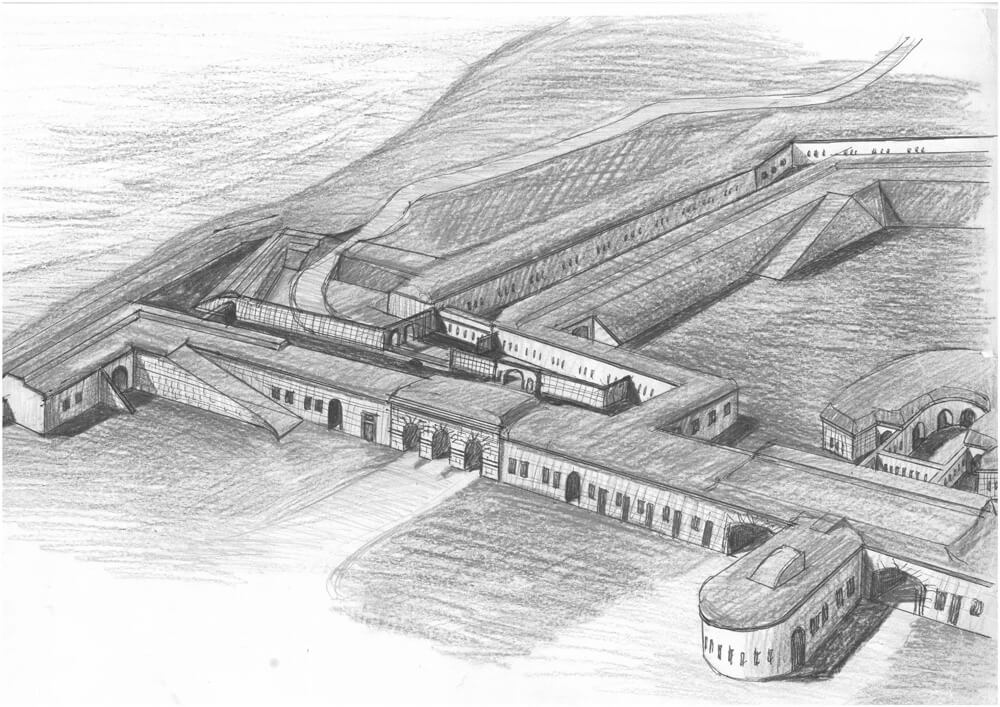

Graphic reconstruction of Bastion VII

THE VÁH-BRIDGEHEAD AND THE DANUBE-BRIDGEHEAD

Vývoj oboch predsunutých pevností (predmostí)27 As early as 1555, the war councillors planned to build a palisade on the left bank of the river Váh, which would be connected to the Old Fortress by a pontoon bridge. However, the war council passed a resolution only in 1577 to build a palisade which could hold 100 horsemen. The work started in 1585. In the first decades – and even in 1649 – the building was called St Nicholas and later St Philip palisade. It was demolished in 1661, as it did not suit the requirements of that period, and in its place a new and stronger palisade was built. In the second half of the 17th century the Jesuits built a chapel in honour of their saint. In 1866, when the biggest work was done, the central part of the fortress was the star-shaped fortress. The rest of the ramparts were probably located according to the previous plan of the palisade. The highest level of the bastions (upper terrace) was asymmetrical due to the cuttings in the salients (summits of the bastions). At the highest point of the bastion, where two ramps led, a gun-site was placed. The upper terrace could also be approached on two ramps. In the central fortress a four-winged, rectangular shaped closed building complex was built, which most likely served as a barrack. From two sides of the star-shaped central fortress – toward northwest and southeast – a chain of fortifications spread, with three bastions in both directions. This chain of fortifications spread from the bank of the Váh toward bastion II of the central fortress, while on the other side of the fortress it spread from bastion III toward the mouth of the river Váh. The plan of the bastions was asymmetrical pentagon or hexagon. On the ledges of the upper terrace gun-positions were built. The bridge-head could be approached on a pontoon bridge from the central fortress. Unfortunately this bridge-head can be only seen in ruins now. 1585. The other ramparts were probably placed according to the plan of the previous palisade. 28. The Danube bridge-head (Fort Star) is situated on the right bank of the river, opposite the eastern bastion of the Old Fortress.29. It was built at the same time as the Váh bridgehead. In the second half of the 17th century the Jesuits also built a chapel here, commemorating St. Peter.

This fortress was also neglected after the Turkish rule ended. However, the bastions built from earth were still there in 1810.

28. Kecskés L.:c.d. str.214.

29. Takács S.:Rajzok a török világból. II. zväzok. Budapest 1915, str.28.

30. Po dobytí najdôležitejších pevností: Nových Zámkov, Levíc a Nitry Turkami, vypracoval vojenský inžinier a architekt J. Priami v roku 1663 v službách cisára návrh na opevnenie Komárna, Červeného Kameňa, Nových Zámkov a Bratislavy. Tieto návrhy môžeme konfortovať s medirytinou Schnitzera podľa návrhu J. Priamiho-1665, ktorá zobrazuje plán opevnenia Bratislavy z roku 1663, ďalej s kartografickým obrazom opevnenia pri Kolárove (Gúta), ktorého medirytinu vyhotovil C. Merian podľa Priamiho Nákresov v roku 1672.

FORT SANDBERG /FORT MONOSTOR /

Bird’s eye view of Fort Sandberg (Monostor)

FORT IGMÁND

Bird’s eye view of Fort Igmánd

THE ANALYSIS OF THE BUILDING METHODS

The Military Hospital next to the County House – at present Park of M. R. Štefánik in its place

The Headquarters’ Building erected in 1815 (photo from 1919)

Bratislava Gate of bastion I – classicism

Gúta Gate of bastion III – neo renaissance

Apáli Gate of bastion VII – romanticism

Líca na hrote zvierajú 145° uhol

Nárožie bastiónu má 110° uhol

The former Military Church (photo from 1915)

Gunnery drill from the early 20th century next to Bastion II of the Palatine Line

Gúta Gate of Bastion III

Army barracks in the New Fortress

1° jedna siaha = 195,000 cm = 6’ šesť stôp

1’ jedna stopa = 32,500 cm = 12” dvanásť palcov

1” jeden palec-cól = 2,700 cm = 12’” dvanásť liniek

1’”jedna linka = 0,225 cm

t.j. 1°=6’=72”=864’”

(Rozpis siahovej miery podľa A. Romaňáka: Pevnost Terezín. Ústí nad Labem 1972.)

34.. Nápis na architráve západného priečelia Bratislavskej brány: FERDINANDUS i. IMPERATOR AUSTRIAE HUNGARIAE REX H.N.V.

THE PRESENT FUNCTION AND EXISTING STATE OF THE MONUMENT

Restoration works in Bastion VI

Lapidary in the restored Bastion VI with artefacts from the Roman imperial period

The restored ramparts of Bastion VI

Leopold Gate during the restoration works

• Vo veľkosti – rozsahu objektov, ktoré boli schopné pojať 200 000 člennú armádu. Najsilnejšia a najväčšia habsburská pevnosť Rakúsko-Uhorskej monarchie – útočisko cisára.

• Pevnosť nikdy nebola dobytá – ani v období tureckých obliehaní v 16. a 17. storočí, ani počas revolučných rokov 1848-49.

• V navrstvení viacerých vývojových etáp budovania bastiónových pevností.

• V monumentálnosti a v spôsobe technického ako aj architektonického riešenia.

• V dobrom stavebno-technickom stave zachovaných objektov, ktoré môžu po revitalizácii spĺňať funkcie nadregionálneho charakteru.

Stavebná činnosť na objektoch novej pevnosti.

Rekonštrukčné práce na objekte Prachárne v Novej Pevnosti

1° jedna siaha = 195,000 cm = 6’ šesť stôp

1’ jedna stopa = 32,500 cm = 12” dvanásť palcov

1” jeden palec-cól = 2,700 cm = 12’” dvanásť liniek

1’”jedna linka = 0,225 cm

t.j. 1°=6’=72”=864’”

(Rozpis siahovej miery podľa A. Romaňáka: Pevnost Terezín. Ústí nad Labem 1972.)

34.. Nápis na architráve západného priečelia Bratislavskej brány: FERDINANDUS i. IMPERATOR AUSTRIAE HUNGARIAE REX H.N.V.

Slovník vybraných termínov

ARMOVANIE

- obmurovanie zemného pevnostného prvku tehlovým alebo kamenným murivom za účelom jeho spevnenia

BANKET

- nachádza sa nad ochodzou, asi 1–1,5 m široké postavenie pre peších strelcov na hradbách. Obrancov rozostavaných na bankete chránila pred paľbou útočníka predprseň (vysoká asi 1,5 m a mierne odklonená od vertikály pre pohodlnejšiu polohu strelca).

BARBETA

delostrelecké postavenie na hradbách alebo valoch, chránené spredu predprsňou a z oboch strán traverzami

BASTIÓN

päťboká pevnostná stavba, ktorá mala na rozdiel od polkruhového rondelu rovné bočné a lícne strany, vďaka čomu sa dala lepšie brániť paľbou pred nepriateľom. Ku kurtíne priliehali boky tvoriace vstup, čiže hrdlo. Vonkajšie strany sa nazývajú lícom.

BATARDEAU

priečna murovaná hradba, deliaca priekopu na úseky, ktoré bolo možné samostatne brániť. Vyskytuje sa v plnom alebo dutom prevedení. V druhom prípade ňou prechádzala galéria, ktorá mohla mať strieľne na obranu priekopy a zároveň umožňovala krytý presun obrancov do vonkajších článkov opevnenia. Niekedy hovoríme aj o krytej kaponiere.

CITADELA

pôvodne samostatná tvŕdza (hrad), ovládajúca staroveké alebo stredoveké mesto; neskôr samostatné jadro bastiónovej pevnosti. V 19. storočí vlastná pevnosť uprostred prstenca tvŕdzí (fortov).

CARNOTOV MÚR

voľne stojací obranný múr opatrený strieľňami (systém Lazara Carnota: zemný val v kombinácii s voľne stojacím múrom)

ČEPIEC (franc. bonnet)

val, ktorý sa navršoval na vystupujúcich hrotoch, najčastejšie na vale krytej cesty. Hrebeň čepca presahoval hrebeň základnej hradby, zastieral protivníkovi výhľad a znemožňoval výstrel do priestoru krytej cesty.

ČIARA OBRANY

predĺžená priamka líc bastiónov. Podľa Daniela Speckleho (1536–1589) boky bastiónov majú byť z hľadiska obrany kolmé na čiaru obrany.

ENVELOPA

predsunutý val či hradba pred bastiónovými frontami, ktorá vznikla spojením kontragard v súvislú líniu

ESKARPA

(škarpa) – v tal. lit. scarpa – čelná strana kurtíny armovaná múrom

ESPLANÁDA (RAYON)

predpolie pevnosti podliehajúce prísnym vojenským predpisom, ktoré určovali, v akej vzdialenosti od fortifikačných prvkov sa môžu stavať civilné budovy (zóna obmedzenej výstavby). Podobný priestor oddeľoval citadelu od ostatných pevnostných objektov.

FAUSSE BRAYE

nízky val predsunutý pred kurtínu, bastión alebo ravelín. S obľubou používaný v holandskej škole.

FLANKOVANIE

bočná paľba, bránenie bočnou paľbou

FORT

predsunutý samostatný pevnostný objekt schopný kruhovej obrany, ktorý nebol so susednými pevnostnými objektami spojený v súvislú pevnostnú líniu

GALÉRIE

kryté chodby v kurtínach alebo v iných fortifikačných článkoch. Niekedy sú opatrené strieľňami smerujúcimi do priekopy. Do delostreleckých kazemát viedli komunikačné galérie. Hlavné galérie viedli v kontreskarpe.

GLACIS

val krytej cesty. Mal tvar pilového kotúča. Od hrebeňa sa mierne zvažoval do predpolia a umožňoval obrancom zrakom i paľbou ovládať blízke okolie hradieb.

KAPONIÉRA

(franc. caponiérie) – priečna hradba v priekope, ktorá spájala poterny klieští s hradbami ravelínov. Bola to v podstate krytá cesta, ktorá spájala fortifikačné články v zavodnených priestoroch.

KAPITÁLY

myslené čiary, ktoré viedli zo stredu opevneného priestoru do predpolia cez hroty bastiónov

KAVALIER

nástavba na bastiónoch alebo kurtínach. Jeho líca a boky sú paralelné s lícami a bokmi bastiónov. Spočiatku to boli zemné valy z čelnej strany armované múrom.

KAZEMATA

(“casa armata”– zbrojný dom) – murované palebné postavenie so zemným násypom alebo v telese valu. Slúžila i na ubytovanie pevnostnej posádky alebo na uskladnenie dôležitého zbrojného materiálu.

KLIEŠTE (TENAILLE)

hradba tvarom pripomínajúca otvorené kliešte mala chrániť kurtínu a spolu s ravelínmi vytvárala súvislú obrannú líniu v priekope

KONTRESKARPA

(v tal. teor. lit. contra–scarpa)– eskarpe protiľahlý múr z vnútornej strany priekopy

KONTRAGARDA

predstavuje val predsunutý pred bastión, ktorého líca sú paralelné s lícami bastiónov. Chránila líce a hrot bastiónu.

KORDON

kamenná rímsa ukončujúca armovanie eskarpy a kontreskarpy

KORUNNÁ HRADBA (KRONWERK)

pozostáva z jedného stredného a dvoch polobastiónov zriadených na krídlach kurtíny – komárňanská Nová pevnosť v 19. storočí

KRYTÁ CESTA

cesta na vnútornej strane glacisu pozdĺž kontreskarpy široká asi 10 m (v tal. teor. lit. strada coperta – strada da sortire)

KUFOR

synonynum pre dvojitú kaponiéru, v prípade použita pri bastiónových opevneniach sa jedná o zabezpečené komunikácie k predsunutým objektom

KURTÍNA

spojovacia hradba medzi dvoma bastiónmi. Názov pochádza z talianskeho slova cortina.

KYNETA

drenážna struha v priekope slúžiaca k odvádzaniu dažďovej vody i k dokonalému odvodneniu priekopy po zrušení jej zaplavenia

LUNETA

samostatná hradba umiestnená v predpolí pred valom krytej cesty v smere bastiónových kapitál. Nemala veľké rozmery a svojím tvarom pripomínala polmesiac. Buggenhagenova luneta.

NUEBAUEROVA LUNETA

pevnôstka na zhromaždiskách umiestnených v ich hrdle. Tieto lunety presahovali prednú plochu zhromaždiska.

MÍNERI

členovia útočného vojska podkopávajúci hradby (mínerovou cestou) kliesnili cestu pevnostným valom podmínovaním. Aj brániace vojsko malo svojich mínerov pre opačný postup. Niektoré pevnosti majú pre tento účel už vopred vybudované tzv. minérske chodby. Odpočúvacie chodby sú galérie slúžiace obrancom k sledovaniu nepriateľských zemných prác.

OCHODZA

slúžila ako cesta na valoch, na ktoré sa vychádzalo rampami. Jej šírka je asi 10 m a vedie po celom obvode vnútorných hradieb.

PALISÁDA

hradba zo zahrotených drevených kolov kolmo zatlčených husto vedľa seba. Palánky sú palisády okolo palebného postavenia delostrelectva.

PAS DE SOURIS

myšie schody – schodisko v armovaní kontreskarpy umožňujúce obrancom prístup z priekopy na krytú cestu

POLMESIAC

hradba, nazvaná podľa tvaru polmesiaca (tal. mezza luna), bola umiestnená v priekope pred hrotom bastiónu

POTERNA

výpadová brána v kurtíne, ako i brána spájajúca jednotlivé fortifikačné články pevnostného systému

PREDMOSTIE

pevnostné zabezpečenie opačného brehu rieky oproti pevnosti (citadely). Úlohou predmostia bola predovšetkým obrana prístupu k mostu. Môže to byť aj samostatná predsunutá pevnosť.

PREDPRSEŇ

zemný val, ktorý slúžil k ochrane strelcov rozmiestnených na bankete. Tiež čelná strana barbety.

RAVELÍN

(v tal. teor. lit. riuellino) – fortifikačný prvok v priekope pred kurtínou medzi dvoma bastiónmi v trojbokom alebo päťbokom tvare. Stavitelia ho s obľubou používali na zabezpečovanie mestských brán. Nahrádzal niekdajšie barbakány.

REDAN

predstavoval trojbokú hradbu, ktorá vystupovala zo stredu kurtíny s hrotom do priekopy. Palebné smery tohto článku boli namierené do priekopy pred líca bastiónov. V 18. a 19. storočí boli budované aj línie redanov spájané priamo úsekmi valov.

REDUIT

uzavretá fortifikačná stavba s kruhovým, štvorcovým alebo polygonálnym pôdorysom. Zo začiatku sa zriaďoval spravidla uprostred ravelínu ako zemný útvar armovaný múrom, v neskoršej dobe sa vyvinul v dokonalú, kazematami vybavenú pevnôstku.

RETRANCHEMENT

bol umiestnený v hrdle dutého priestoru bastiónu alebo ako nadstavba na bastiónoch, ktorá sa skladala z dvoch polobastiónov, spojených kurtínou. Jeho hrebeň presahoval z taktických dôvodov horizont bastiónu. Neskôr bol v retranchementoch zriadený rad kazematných priestorov.

ROHOVÁ HRADBA – (HORNWERK)

skladá sa z dvoch polobastiónov zriadených na krídlach kurtíny

STRUHA

dláždená rýha (kyneta), ktorá slúžila na odvádzanie dažďovej vody z priekop, ako aj na ich zavodnenie

ŠIANCE

všeobecné označenie pre poľné opevnenie, najmä pre zemné valy

TABLETTE

nízky múrik nad kordónom, ktorý zvyšoval armovanie eskarpy za účelom spevnenia predprsne

TALUS

spevnenie vnútornej strany hradby alebo valu pevnostného objektu. Tiež vnútorná strana (svah) telesa bokov a líc bastiónu.

TRAVERZY

priečne hradby na krytej ceste, ktoré ju členili na kratšie úseky. Slúžili tiež na bočnú obranu krytej cesty.

UŠNICA (ORILLON)

delostrelectvo na bokoch bastiónov chránili pred paľbou z predpolia vyčnievajúce “krídla”, nazývané tiež “uši”. “Ušnicový” bastión je typický pre taliansku školu.

VALOVÁ CESTA

ochodza – krytá cesta po celom obvode vrcholu hradieb pevnosti (na kurtínach, telesách líc a bokov bastiónu), na ktorú sa vychádzalo rampami

ZHROMAŽDISKO

rozšírený priestor vo vystupujúcich, ale hlavne v zbiehajúcich sa uhloch krytej cesty (nemecky “Waffen Platz”)

ZOZNAM POUŽITEJ LITERATÚRY

Bochenek Ryszard: Od palisád k podzemním pevnostem. Praha 1972.

Filous Jozef: Pevnost Komárno – několik poznámek k minulosti.

Svaz čs. rotmistrů – odbočka v Komárne. Komárno 1930.

Gerő László: Magyarországi várépítészet. Budapest 1955.

Kecskés László: Komárom erődrendszere.

Műemlékvédelem XXII. évfolyam, 3. szám. Budapest 1978.

Kecskés László: Komárom az erődök városa. Budapest 1984.

Kolektív autorov: Súpis pamiatok na Slovensku, zväzok II. Bratislava 1968.

Lichner Ján: Stavebný charakter mestských hradieb a opevnení za čias tureckého nebezpečenstva na Slovensku.

Vlastivedný časopis XIII/1. Bratislava 1964.

Romaňák Andrej: Pevnost Terezín. Ústí nad Labem 1972.

Rovács Albín: A Komáromi vár leszerelése. Komáromi Lapok XXII/30. Komárno 1901.

Szinnyei József: Komárom 1848/49-ben. Budapest 1887.

Takács Sándor: Lapok egy kis város múltjából. Komárom 1886.

Tok Vojtech: Komárňanská pevnosť. Komárno 1974.

Závadová Katarína: Verný a pravý obraz slovenských miest a hradov ako ich znázornili rytci a ilustrátori v XVI., XVII. a XVIII. storočí. Bratislava 1974.